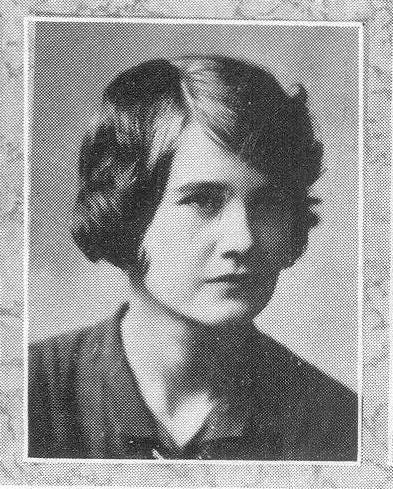

My mother’s high school senior picture often captured my attention. As a child, I found it odd to look at her young face with porcelain skin topped with wavy brown hair looking so drastically different from the mom I knew. As an adult, what struck me about the photo was entirely more expansive than the child’s view. Her photo was snapped in 1926, in the rural midwest, a 17-year old girl in a graduating class of 49 students. She looked calmly and directly into the camera but with a sideways glance as if she had just turned to look over her shoulder at someone beckoning her.

It was the quotation beside her photo that always haunted me. Each senior had the same question imprinted under their senior photo asking “What are your ambitions?”. Most high school seniors throughout eternity use that moment of their senior year to list their many credentials, clubs, activities, sports and awards they had garnered during their four years, to gain as much notoriety as possible. But not my mother. She had responded succinctly , “to remain silent”.

In younger years, I’m sure I just rolled my eyes with mild annoyance at this, confirming that my mother was never intended for anything great at a time when I wanted an educated, upwardly mobile mother with a career. A woman who rocked the boat, had her own personal goals outside of her family, one who would even, perhaps, crusade for women’s rights. What I had was a simple, sweet mom who wore an apron, grew a garden and canned vegetables. Her identification came through her family and children. And it wasn’t until I hit my fifties and was blindsided by the recovered memories of incest, struggled through menopause and multiple health issues, had mothered my own child to adulthood that I emerged a wiser woman who began to understand the meaning behind her words.

Silence was the vow that many women took in our family. The vow came in many forms; unspoken, implied, cloaked in ignorance, violently enforced. Whether you were a woman born into this type of family, or married into it, or just witnessed it from across the road, the women knew to never, ever speak or challenge the men in our world. This pathology gripped many families in this time and place. But the injustices didn’t just come to the women. Both genders of their children were susceptible, wild animals and pets were victims, and rarely but sometimes, even the men themselves turned on each other. Any and all destructive behavior was to be tolerated, the only thing intolerable was to speak of it.

In looking back over my mother’s life, I’m not sure how she managed her silence. Or if she even needed to. Surely, she hadn’t been born without the innate desire to bloom, to speak, to honor herself. I invariably pictured her silence as a conscious push of the mute button. But perhaps the concept of a life where she was more than a body bearing babies or a submissive housewife never quite bubbled to the surface for her.

My mother wasn’t a drinker so she didn’t have the sweet numbness that alcohol gives. She didn’t visit the doctor for “nerve pills” as droves of women did during the time after WWII and before women’s lib. She didn’t subscribe to church or the old-timey ways of following God, so she didn’t even have the oppression of organized religion to keep her in line. And although physically active on a farm, she didn’t perform the heavy manual labor allocated to the men therefore didn’t have the benefit of exhaustive physical work. Over time, I’d concluded that she possessed some miraculously effective form of self suppression; part stoic German genes, part learned submissive behavior.

I, on the other hand, was the complete opposite. By the time I was in my thirties, I had successfully alienated almost everyone in my family. They had barely tolerated me as the child who oozed emotion, the young adult in college raising hell and joining the revolution, the adult woman who moved far, far away, refusing to accept the indoctrination I’d been exposed to as a child. What had often been disclosed to me, often with thinly veiled contempt, was that I was the wild child who yelled and screamed the most, wet the bed almost nightly, sang the loudest, exhibited the most riskiest behaviors, asked the most incessant questions, received most of the spankings and blame, the “crybaby” who cried the longest. Most of the other children in our brood, learned quicker than I did, how to suppress and deny their feelings. This seemed impossible for me. If there was an injustice anywhere, I screamed about it. If a sibling or animal was the target of an adult’s rage, I was right there in the middle of the conflict even as the witnessing adults looked on in a blank stupor of denial.

Apparently, I not only used my voice often but also staged revolutions against the adults. I encouraged my siblings and cousins to refuse to comply to meal or bedtime requests, once even writing and performing a vignette complete with lyrics, depicting all the methods we as children, had available to us, to commit suicide and end the cruelty. My oldest sister said I was the spookiest child she’d ever known.

But it never seemed odd for me, even as a young child, to want to empower myself and others because I recognized the cruel and oppressive tendencies of silence and pathology attempting to shroud us. My family had inadvertently raised a warrior, instead of a follower and my battles seemed as important to fight then as it continued to be throughout my adult years.

By some divine flip of the switch, some quirk in the cosmos, be it from my own DNA or divine intervention and presence, I was spared the ability to silence myself. I had somehow failed to inherit the part of my family’s ancestry that kept me quiet. I, unlike my mother, lacked the capability to learn “to remain quiet”.

One of the most monumentally difficult steps of my life was to leave my family of origin, toss aside their cloistered and cult-like thinking, shed the skin of ignorance. It was an act of liberation, an exercise in blind faith, filled with transcendence combined with sheer terror. The process of erasing the imprint of abuse is a huge, all encompassing life task and one born of absolute necessity if one desires a decent life. It required gut wrenchingly hard work to reprogram myself, body and soul, in physical, psychological and spiritual manners. It required the devotion of my lifetime and the lifetime of my daughter, a process that continues to require growth and adaptation. But it’s often the tough and arduous decisions that give us the sweetest rewards. Those that propel us forward and farthest, generally point us in the most difficult of directions toward the path we would have never consciously chosen if given any other choice.

If I hadn’t been given the gift of voice, I would have been a child of silence. If I hadn’t repulsed and screamed at injustices, I wouldn’t have learned to advocate for myself and my child. If I hadn’t known the trauma of abuse, I wouldn’t have developed the keen sensitivities necessary for survival and compassion for its victims. If I hadn’t walked in the darkest of times, I wouldn’t understand the complexities of depression, anxiety, PTSD and mental illness. If I wasn’t forced, kicking and screaming, to take this journey completely on my own, I wouldn’t have discovered my core of inner strength and the ferocity of the woman inside.

I often think of my mother. I used to feel so sad and powerless for her. I cringed at the thought of her wordless, mute existence. I ached for all the unexpressed feelings she held inside. But as of late, I’ve come to understand that she communicated well with me through her actions, in ways that words fall short. Perhaps she showed me what NOT to imitate in life. Maybe her path of a voiceless existence shrieked so loudly of self-betrayal, that I paid attention and followed another path. And her ultimate gift to me, one that I thank God for every day, is that I never, ever learned “to remain quiet”.